This is Part Three of a series, Women in the Workforce: We Can Do It!, exploring topics related to the history, challenges, and accomplishments of working women in America. Topics to date include: Women in the Workforce: We Can Do It!, War Opens the Doors for Working Women

Post WWI: The Man's Income is The Family's Income. After the war, married women went back to working in the home. Only 10% of married white women, including new immigrants, worked outside of the home.

Post WWI: The Man's Income is The Family's Income. After the war, married women went back to working in the home. Only 10% of married white women, including new immigrants, worked outside of the home.

There was a societal belief that a man’s income was the family income, and therefore there was no need for married women to have a job. Black families did not have that luxury, and married black women continued to work outside of the home due to financial necessity.

There was a societal belief that a man’s income was the family income, and therefore there was no need for married women to have a job. Black families did not have that luxury, and married black women continued to work outside of the home due to financial necessity.

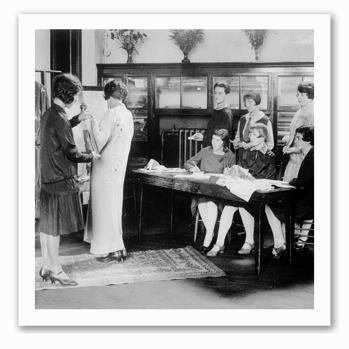

Single women, however, stayed in the workforce, and their employment increased during the 1920s. It was the age of the flappers and young, single women represented this lifestyle with increased independence. As more people moved to the cities, more jobs were available to women. Traditional female jobs, such as teachers, nurses, and librarians, continued to be popular, but the rise of corporate offices brought about new opportunities. Young, ambitious women found work in the cities as typists, filing clerks, and secretaries. The pictures of many women working behind desks were common during this time, and although the work was mundane, it was better than working in the mills or farms.

Buying Power of Women is Recognized. Consumerism increased in the 1920s. Household appliances, cosmetics, and clothing advertisements targeted women, and working women used their financial independence to buy these goods. An advertisement in the Chicago Tribune expressed that “Today’s woman gets what she wants, the vote, slim sheaths of silk to replace voluminous petticoats, glassware in sapphire blue or glowing amber, the right to a career, and soap to match her bathroom’s color scheme.” Consumerism also brought about new career opportunities. Department stores in the 1920s hired women in large numbers to sell products and to work as buyers and designers.

Buying Power of Women is Recognized. Consumerism increased in the 1920s. Household appliances, cosmetics, and clothing advertisements targeted women, and working women used their financial independence to buy these goods. An advertisement in the Chicago Tribune expressed that “Today’s woman gets what she wants, the vote, slim sheaths of silk to replace voluminous petticoats, glassware in sapphire blue or glowing amber, the right to a career, and soap to match her bathroom’s color scheme.” Consumerism also brought about new career opportunities. Department stores in the 1920s hired women in large numbers to sell products and to work as buyers and designers.

Although there were more opportunities for women in the 1920s, the goal for young women was still marriage. Jobs were often seen as an opportunity to meet men and secure a proposal. The flappers of that era, with their short hair and short dresses, still knew that their ultimate goal was to be a wife. They may have danced, drank, smoked, and worked as secretaries, but for most white women during this time, that sense of independence would be short-lived. Education and jobs were viewed as a precursor to marriage. In fact, Henry Ford once said, “I pay our women well so they can dress attractively and get married.”

Societal Expectations Prevail. The general expectation was that men were the breadwinners and women tended to the home. If women did work outside of the home, then it was to have some extra fun money or to pursue a personal interest.

With that in mind, it was only natural for women to be paid less than men. Cultural norms persisted, and most Americans approved of paying men higher wages for the same job, and most agreed that women should not work once married. This societal ideal of the American family was far from the truth. Many women needed to work to help their families put food on the table, and many women were the sole breadwinners. Unequal treatment in the workplace was detrimental to many households.

With that in mind, it was only natural for women to be paid less than men. Cultural norms persisted, and most Americans approved of paying men higher wages for the same job, and most agreed that women should not work once married. This societal ideal of the American family was far from the truth. Many women needed to work to help their families put food on the table, and many women were the sole breadwinners. Unequal treatment in the workplace was detrimental to many households.

The Impact on Black Women. Although the 1920s was a time of prosperity, by the end of the decade, 59% of American families could not make enough money for even a minimal standard of living, and African American families were especially impacted. Black women in the North had approximately the same literacy rate as white women, but the payoff was much lower. Even though Black women were similarly educated and worked for less wages, employers refused to hire them. Most Black women were limited in their work choice to factories or domestic services. In 1900, African Americans accounted for one-fourth of the domestic workers, and by 1930, that number rose to one-half. Employment agencies even traveled to the South to recruit women to the North to work as servants, offering them jobs and transportation. The majority of the 750,000 blacks who moved north during the Great Migration in the 1920s were women. In New York City, there were 10 Black women for every 8.5 men.

Limited Job Opportunities & Wage Disparity Continues. By 1929, more than a quarter of all women, and more than half of all single women, were working outside of the home. Not only were job opportunities limited, but the pay disparity was great. In factories, male workers in 1920 started at 40 cents per hour, while women started at 25 cents. The average weekly wage for a man was $29.35, and for a woman, it was $17.34. Society liked to think that young women were only working for the short term before marriage, so the wage disparity was not a cause for much concern.

Women in the Workforce: We Can Do It!

Whether married or single, with children or not, working part-time, full-time, or even two jobs, as a stay-at-home mom or a community volunteer, American women can do it! Throughout history, American women always have. And I am so proud we do!

Over the next few months, I will explore how topics about women in the workforce from the early 1900s until the present. Also, I want to note the changing trends of women in the workforce that this series contemplates will focus on white, middle-class women. Women of color have had very different experiences, and their work lives have been defined by racism, sexism, and financial necessity. I have pointed this out when possible, but please keep in mind that this series is not a complete picture of all women.

Please check back to read the next blog in the series, Women in the Workforce: We Can Do It! as we explore The Great Depression & Pay Disparity.

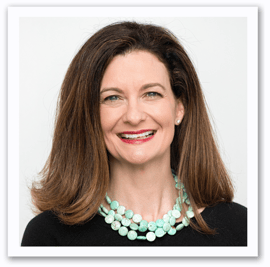

Propel HR President Lee Yarborough

“My father, Braxton Cutchin, and I founded the company in 1996. After being in the PEO and HR world for 25 years, I have experienced firsthand the value we can provide to both the clients and the employees. It is truly a win for all parties. I’m proud to have helped establish Propel HR as an industry forerunner in the Southeast. There is nothing I love more than receiving phone calls from clients who seek my advice as a trusted advisor. This is a business where I feel that I can help others, and that is important to my own value.”

“My father, Braxton Cutchin, and I founded the company in 1996. After being in the PEO and HR world for 25 years, I have experienced firsthand the value we can provide to both the clients and the employees. It is truly a win for all parties. I’m proud to have helped establish Propel HR as an industry forerunner in the Southeast. There is nothing I love more than receiving phone calls from clients who seek my advice as a trusted advisor. This is a business where I feel that I can help others, and that is important to my own value.”

-- Lee Yarborough, President, Propel HR

Active in many professional and community organizations, Lee recently served as Chair of the Board of Directors of the National Association of Professional Employer Organizations (NAPEO). As NAPEO Chair, Lee focused on diversity and initiatives to deepen member relations. Under her leadership, she formed Women in NAPEO (WIN), a networking group designed to engage, empower, and encourage women working in the PEO industry. On the local level, Lee also served as the Chair of NAPEO’s Carolinas Leadership Council for more than a decade. In 2015, she was named a Fellow of the eleventh class of the Liberty Fellowship Program and a member of the Aspen Global Leadership Network.

An advocate for public education, Lee has served on the executive board as Chair of Public Education Partners and is the founder and director of Read Up Greenville, a young adult, and middle grades book festival in downtown Greenville, SC.

When she breaks from board meetings, client visits, and networking, most likely, you will find Lee reading, camping, or spending time with her family. She also enjoys volunteering at her church and staying involved with her children's schools.

About Propel HR. Propel HR is an IRS-certified PEO that has been a leading provider of human resources and payroll solutions for 25 years. Propel partners with small to midsized businesses to manage payroll, employee benefits, compliance and risks, and other HR functions in a way that maximizes efficiency and reduces costs. Visit our new website, www.propelhr.com.

About Propel HR. Propel HR is an IRS-certified PEO that has been a leading provider of human resources and payroll solutions for 25 years. Propel partners with small to midsized businesses to manage payroll, employee benefits, compliance and risks, and other HR functions in a way that maximizes efficiency and reduces costs. Visit our new website, www.propelhr.com.